Johnnetta Betsch Cole, Ph.D., President 2018-2022

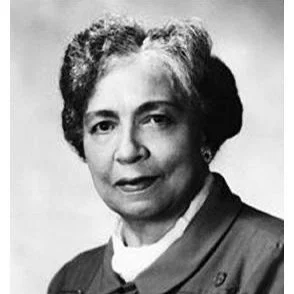

Dr. Dorothy Irene Height, President 1957-2010

Mary McLeod Bethune, Founder & President 1935-1949

Ingrid Saunders Jones, President 2012-2018

Vivian Carter Mason, President 1953-1957

Barbara Shaw, President 2010-2012

Dorothy Boulding Ferebee, President 1949-1953

-

Johnnetta Betsch Cole is a noted educator, author, speaker and consultant on diversity, equity, accessibility and inclusion in educational institutions, museums and other workplaces. After receiving a Ph.D. in anthropology, Dr. Cole held teaching positions in anthropology, women’s studies, and African American studies at several colleges and universities. She served as President of both historically Black colleges for women in the United States, Spelman College and Bennett College, a distinction she alone holds. She also served as the Director of the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art, as a Principal Consultant at Cook Ross, and as a Senior Consulting Fellow at the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Dr. Cole is currently the Chair and Seventh President of the National Council of Negro Women, an advocacy organization for women’s rights and civil rights. She serves as Special Counsel on Strategic Initiatives at the Baltimore Museum of Art. She has received numerous awards and is the recipient of 70 honorary degrees. Throughout her career and in her published work, speeches, and community service, Johnnetta Betsch Cole consistently addresses issues of race, gender, and all other systems of inequality.

-

An extraordinary educator and political leader, Mary McLeod Bethune (1875-1955), founded NCNW in 1935 as an "organization of organizations" to represent national and international concerns of Black women. NCNW fought for jobs, the right to vote, and anti-lynching legislation. It allowed Black women to realize their social justice and human rights goals through united and constructive action.

Founder of Bethune-Cookman University, Mary McLeod Bethune, is one of America's most inspirational daughters. Educator. National civil rights pioneer and activist. Champion of African American women's rights and advancement. Advisor to Presidents of the United States. The first in her family not to be born into slavery, she became one of the most influential women of her generation.

Dr. Bethune famously started the Daytona Literary and Industrial Training Institute for Negro Girls on October 3, 1904, with $1.50, vision, an entrepreneurial mindset, resilience, and faith in God. She created "pencils" from charred wood, ink from elderberries, and mattresses from moss-stuffed corn sacks. Her first students were five little girls and her five-year-old son, Albert Jr. In less than two years; the school grew to 250 students. Recognizing the health disparities and lack of medical treatment available to African Americans in Daytona Beach, she also founded the Mary McLeod Hospital and Training School for Nurses, which at that time was the only school of its kind that served African American women on the east coast.

Daytona Normal would continue to increase in popularity and merged with the Cookman Institute of Jacksonville, Florida, in 1923 and became Bethune-Cookman College.

Tireless, talented, and committed to service, Dr. Bethune held leadership positions in several prominent organizations while also leading her school. In 1935, she founded the National Council of Negro Women, which became a highly influential organization with a clear civil rights agenda.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt appointed her to the National Youth Administration in 1936. By 1939 she was the organization's Director of Negro Affairs, which oversaw the training of tens of thousands of black youth. She was the only female member of President Roosevelt's influential "Black Cabinet." She leveraged her close friendship with First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt to lobby for the integration of the Civilian Pilot Training Program and bring the Program to the campuses of historically Black colleges and universities, which led to graduating some of the first black pilots in the country.

Dr. Bethune was one of the founders of the United Negro College Fund. Her civil rights work helped integrate the Red Cross. She was the only woman of color at the founding conference of the United Nations. Appointed by President Harry S. Truman, she led the US delegation to Liberia for the inauguration of President William V.S. Tubman in 1949. In 1951, she served on President Truman's Committee of Twelve for National Defense. She received an honorary doctorate from Rollins College. And now, in 2022, she will become the first African American to represent a state in the National Statuary Hall in the United States Capitol.

-

Ferebee was born to Benjamin Richard Boulding, a railroad superintendent, and Florence Boulding, a teacher, in Norfolk, Virginia. When her mother became ill, Dorothy went to live with a great-aunt in Boston, Massachusetts, where she graduated from Simmons College in 1920 and was in the top five of her Tufts University Medical School graduating class in 1924.[2]

Ferebee was affiliated with Howard University's Medical school, starting in 1927 as an instructor of Obstetrics, and later as the medical director of the Howard University Health Service from 1949-1968, all while maintaining her own private practice.[3]

She was also instrumental in establishing the Southeast Neighborhood House, an adjunct of the whites-only Friendship House medical center, to provide medical care and other community services to African-Americans in Washington, D.C. She served as the first medical director for the Mississippi Health Project, "a seven year program stands as one the most impressive examples of voluntary public health work ever conducted by black physicians in the Jim Crow South, touching thousands of black Mississippians at a time when they had virtually no access to professional medical care".[4]

She served as the tenth International President of Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority from 1939 until 1941. She then served as the second president of the National Council of Negro Women, from 1949 to 1953, succeeding its founder, Mary McLeod Bethune. She also served as the director of health services at Howard University Medical School from 1949 until 1968. From 1969 to 1972, Dr. Ferebee served at the national fourth vice president of Girl Scouts of the United States of America.

She was the first recipient, in 1959, of Simmons College's Alumnae Achievement Award. The college also awards several scholarships in her name each year.

Ferebee was married in 1930 to a dentist, Claude Thurston Ferebee. He was a Howard University College of Dentistry professor, with whom she had twins, Dorothy and Claude Jr. Ferebee died on September 14, 1980, in Washington, D.C.[5]

In 1990 Washington Highland Elementary School, at 3999 Eighth Street, SE, was renamed Ferebee-Hope Elementary School to honor Ferebee and also Marion Conover Hope.[6] The school was closed in 2013, but the next door recreation center, also named Ferebee-Hope, remained open.[7]

-

At the first biennial convention, held in 1953, the National Council of Negro Women elected its third president, Vivian Carter Mason. Having served as vice president under Ferebee, and having worked closely with Bethune, she was well known to the membership. During Ferebee's extended trips to represent the council at conferences and meetings, both within the United States and abroad, it was Vivian Carter Mason who had chaired the meetings and addressed crucial organizational issues.

Vivian Carter Mason served as NCNW president from November 1953 to November 1957. By 1953, basic program activities were broadly defined under eleven national departments whose titles differed little from the original committees established in the late 1930s. The departments included Archives and Museum, Citizenship Education, Education, Human Relations, International Relations, Labor and Industry, Public Relations, Religious Education, Social Welfare, Youth Conservation, and Fine Arts. The NCNW's special projects and programs tended to reflect the apparent needs of its national affiliates and local councils, and during Mason's administration there was a special emphasis on interracial cooperation.

The NCNW had grown in stature, membership, and influence. Its structure incorporated a rather comprehensive program emphasis; its internal composition included local councils and national affiliates; and its cooperative endeavors, extending to every major program affecting black people, required a national office with the professional expertise and physical resources necessary for administering what had become a large organization. It was the scope of the NCNW's work, not the size of the membership, that defined the necessary level of administration.

Vivian Carter Mason introduced a tighter and more sophisticated administration, and further interpreted the organization's program. The national headquarters became the center in which the council greeted national leaders, hosted social functions, and built coalitions with other national organizations. The building was painted, refurbished, and physically realigned to provide additional office space, privacy, and improved working conditions.

Mason understood constitutional law and the importance of developing an instrument that could govern the organization effectively. Under Mason's administration, the constitution was amended to include additional membership categories such as the Life Members Guild, and to incorporate specific items aimed at curtailing the free-wheeling activities of some local councils and individuals who were acquiring property, soliciting funds, and engaging in partisan political activities not sanctioned by the national office. The NCNW began to require that local councils hold annual elections. Local councils were permitted to structure their own constitutions, with the stipulations that the constitutions conform to the legal scope of the national organization, and that a copy of the document be forwarded to the national office. In 1955 and 1957, revised local council manuals and handbooks for regional directors were distributed to the membership. Mason felt that these materials both explained and enhanced the administrative process.

Vivian Carter Mason was thrust into leadership during one of the most critical and historic periods in American history: on May 17, 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court struck at the heart of the "separate but equal" dictum by ruling that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. Mason's administration was dominated by the civil rights struggle that emerged in the 1950s. The NCNW joined with the NAACP and other national organizations to devise strategies to implement the 1954 Supreme Court decision. Following the court decision, the NCNW met with affiliate presidents and experts in education and group relations to discuss program development throughout the nation. In October 1954, the heads of eighteen national organizations of women met to share information concerning both implementation of the Supreme Court decision and educational programs. Two years later, the twenty-first annual convention was an interracial conference of women. This conference explored how women of all colors and all persuasions could work to surmount barriers to human and civil rights. Other activities included public programs supportive of Rosa Parks, Autherine Lucy, and the Birmingham bus boycott. Mason visited Alabama to acquire first-hand information on the situation there.

During her four years as NCNW president, Vivian Carter Mason succeeded in moving the council to another level. Assessing her administration, she said that many of the goals had not been reached. In her recommendations for the future, she cited a number of areas that needed the immediate attention of the next president. She suggested that the NCNW develop more local councils and strengthen existing ones by continuing to hold the leadership conferences begun in 1952 and by extensively promoting programs; that the NCNW sponsor at least two meetings per year with national affiliates to ensure greater participation and cooperation; and that the council build a strong public relations program. After twenty-two years of operation under three administrations, the NCNW had built a solid base of credibility, had developed an extensive network of contacts and supporters, and had created a sound constitution and operational structure that could easily be amended and expanded. The organization still needed money and clearly defined program service areas.

-

Dorothy Height was a civil rights and women's rights activist focused primarily on improving the circumstances of and opportunities for African-American women.

Synopsis

Born in Virginia in 1912, Dorothy Height was a leader in addressing the rights of both women and African Americans as the president of the National Council of Negro Women. In the 1990s, she drew young people into her cause in the war against drugs, illiteracy and unemployment. The numerous honors bestowed upon her include the Presidential Medal of Freedom (1994) and the Congressional Gold Medal (2004). She died on April 20, 2010, in Washington, D.C.

Early Life

Born on March 24, 1912, in Richmond, Virginia, African-American activist Dorothy Height spent her life fighting for civil rights and women's rights. The daughter of a building contractor and a nurse, Height moved with her family to Rankin, Pennsylvania, in her youth. There, she attended racially integrated schools.

In high school, Height showed great talent as an orator. She also became socially and politically active, participating in anti-lynching campaigns. Height's skills as a speaker took her all the way to a national oratory competition. Winning the event, she was awarded a college scholarship.

Height had applied to and been accepted to Barnard College in New York, but as the start of school neared, the college changed its mind about her admittance, telling Height that they had already met their quota for black students. Undeterred, she applied to New York University, where she would earn two degrees: a bachelor's degree in education in 1930 and a master's degree in psychology in 1932.

Tireless Activist

After working for a time as a social worker, Height joined the staff of the Harlem YWCA in 1937. She had a life-changing encounter not long after starting work there. Height met educator and founder of the National Council of Negro Women Mary McLeod Bethune when Bethune and U.S. first lady Eleanor Roosevelt came to visit her facility. Height soon volunteered with the NCNW and became close to McLeod.

One of Height's major accomplishments at the YWCA was directing the integration of all of its centers in 1946. She also established its Center for Racial Justice in 1965, which she ran until 1977. In 1957, Height became the president of the National Council of Negro Women. Through the center and the council, she became one of the leading figures of the Civil Rights Movement. Height worked with Martin Luther King Jr., A. Philip Randolph, Roy Wilkins, Whitney Young, John Lewis and James Farmer —sometimes called the "Big Six" of the Civil Rights Movement—on different campaigns and initiatives.

In 1963, Height was one of the organizers of the famed March on Washington. She stood close to Martin Luther King Jr. when he delivered his "I Have a Dream" speech. Despite her skills as a speaker and a leader, Height was not invited to talk that day.

Height later wrote that the March on Washington event had been an eye-opening experience for her. Her male counterparts "were happy to include women in the human family, but there was no question as to who headed the household," she said, according to the Los Angeles Times. Height joined in the fight for women's rights. In 1971, she helped found the National Women's Political Caucus with Gloria Steinem, Betty Friedan and Shirley Chisholm.

While she retired from the YWCA in 1977, Height continued to run the NCNW for two more decades. One of her later projects was focused on strengthening the African-American family. In 1986, Height organized the first Black Family Reunion, a celebration of traditions and values which is still held annually.

Later Years

Height received many honors for her contributions to society. In 1994, President Bill Clinton awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom. She stepped down from the presidency of the NCNW in the late 1990s, but remained the organization's chair of the board until her death in 2010. In 2002, Height turned her 90th birthday celebration into a fundraiser for the NCNW; Oprah Winfrey and Don King were among the celebrities who contributed to the event.

In 2004, President George W. Bush gave Height the Congressional Gold Medal. She later befriended the first African-American president of the United States, Barack Obama, who called her "the godmother of the Civil Rights Movement," according to The New York Times. Height died in Washington, D.C., on April 20, 2010.

Former First Lady and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton was among the many who mourned the passing of the famed champion for equality and justice. Clinton told the Washington Post that Height "understood that women's rights and civil rights are indivisible. She stood up for the rights of women every chance she had."

On February 1, 2017, the United States Postal Service kicked off Black History month with the issuance of the Dorothy Height Forever stamp honoring her civil rights legacy.

-

Dr. Barbara Shaw has served as a teacher in the Baltimore City Public School System; a producer with Maryland Public Television; and a prison administrator with the State of Maryland, where she retired after 30 years of service. In December 2009, Ms. Shaw was elected Vice Chair of the National Council of Negro Women, Inc.

Ms. Bethune always used her hand to illustrate her point, "with one finger she said, if I tap you, you may not even know that you have been touched.

With two fingers, she declared, you may well know that you have been tapped. But if I bring all of my fingers together and make a fist I can give you a mighty blow." That mighty blow was not a violent one at each other - it was a recognition that we have each other. We joyfully join together recognizing all the way we need each other and can do more as we are together. We can strike a blow at injustice everywhere.

Building on this council idea, you and I empower ourselves. Keeping connected to one another builds our strength and enhances our power. Today NCNW needs you to be connected and you need NCNW to be connected with women around the world. Our families and communities, and indeed, our nation need the talents and gifts we bring.

As we look ahead, will you think deeply of the value of being an active part or supporter of an organization that stands up for women? Will you stand up for yourself by joining hands with others? Whatever else it does, NCNW offers that opportunity.

The world we envision will be better for us all as we make the Bethune dream and tradition our own.

-

Ms. Ingrid Saunders Jones previously served as Senior Vice President of Global Community Connections for The Coca-Cola Company and Chair, The Coca-Cola Foundation (Atlanta, GA). As the leader of Coca-Cola’s philanthropy efforts, Ms. Jones was responsible for the company’s contribution of more than $460 million to support sustainable community initiatives, including the Hispanic Scholarship Fund, United Negro College Fund (UNCF), Catalyst, the Critical Difference for Women program at Ohio State University, the International Costal Clean-up, Boys and Girls Clubs of America, the National Council of Negro Women and the World Wildlife Fund, to name a few. The Foundation also funds The Coca-Cola First Generation Scholarship Program for first generation college students. Ms. Jones also serves on the boards of The Coca-Cola Africa Foundation and The Coca-Cola Scholars Foundation.

Earlier in her career, Ms. Jones worked with the Honorable Maynard Jackson, then Mayor of the City of Atlanta; served as a legislative analyst for the president of the Atlanta City Council; served as the Executive Director of the Detroit Wayne County Child Care Coordinating Council; and taught in the public schools of Detroit and Atlanta.

Ms. Jones is a board member of Clark Atlanta University, Woodruff Arts Center, Congressional Black Caucus Foundation, The Ohio State University President’s Council on Women, and the Andrew Young School of Policy Studies at Georgia State University. She also is a member of the Rotary Club of Atlanta, the Society of International Business Fellows, and serves on the board of the national board of directors of Girl Scouts USA.

Recognition of her leadership and contributions include the National Council of Negro Women’s 2011 Uncommon Height Award; 2011 Jackie Robinson Robie Humanitarian Award; the 2010 Distinguished Citizen Award from the Boy Scouts of America; the 2010 Corporate Responsibility Award from ESSENCE Magazine; the 2008 Executive Leadership Council’s Achievement Award; The President’s Award from Morehouse College; The Ohio State University Foundation’s John B. Gerlach Development Award; and the Georgia State University School of Business Hall of Fame — among others.

A native of Detroit, Ms. Jones earned a bachelor’s degree in education at Michigan State University and a master’s degree in education at Eastern Michigan University. Michigan State University honored her with an honorary Doctor of Humanities Degree. She also received honorary degrees from Spelman College and Knoxville College.